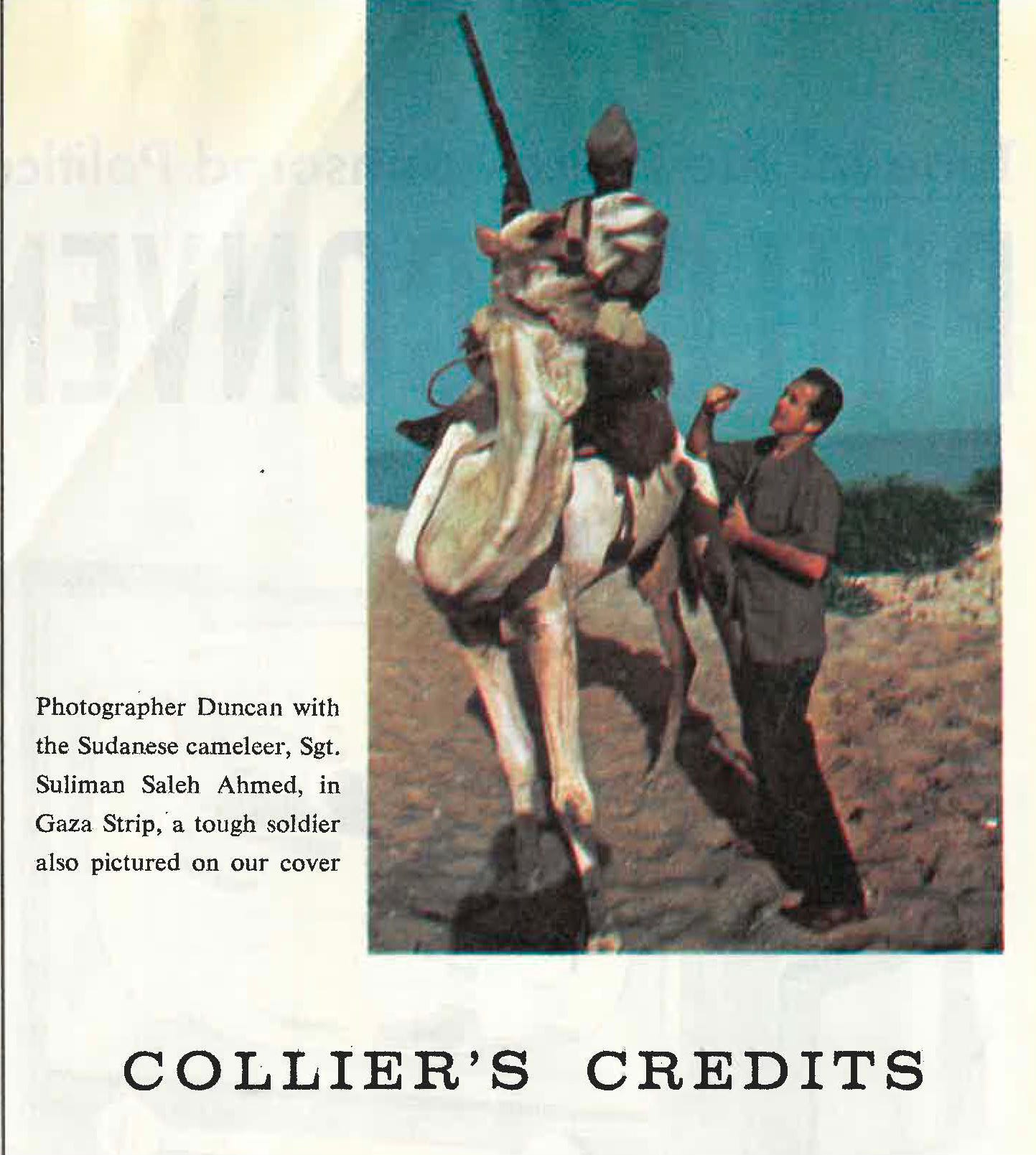

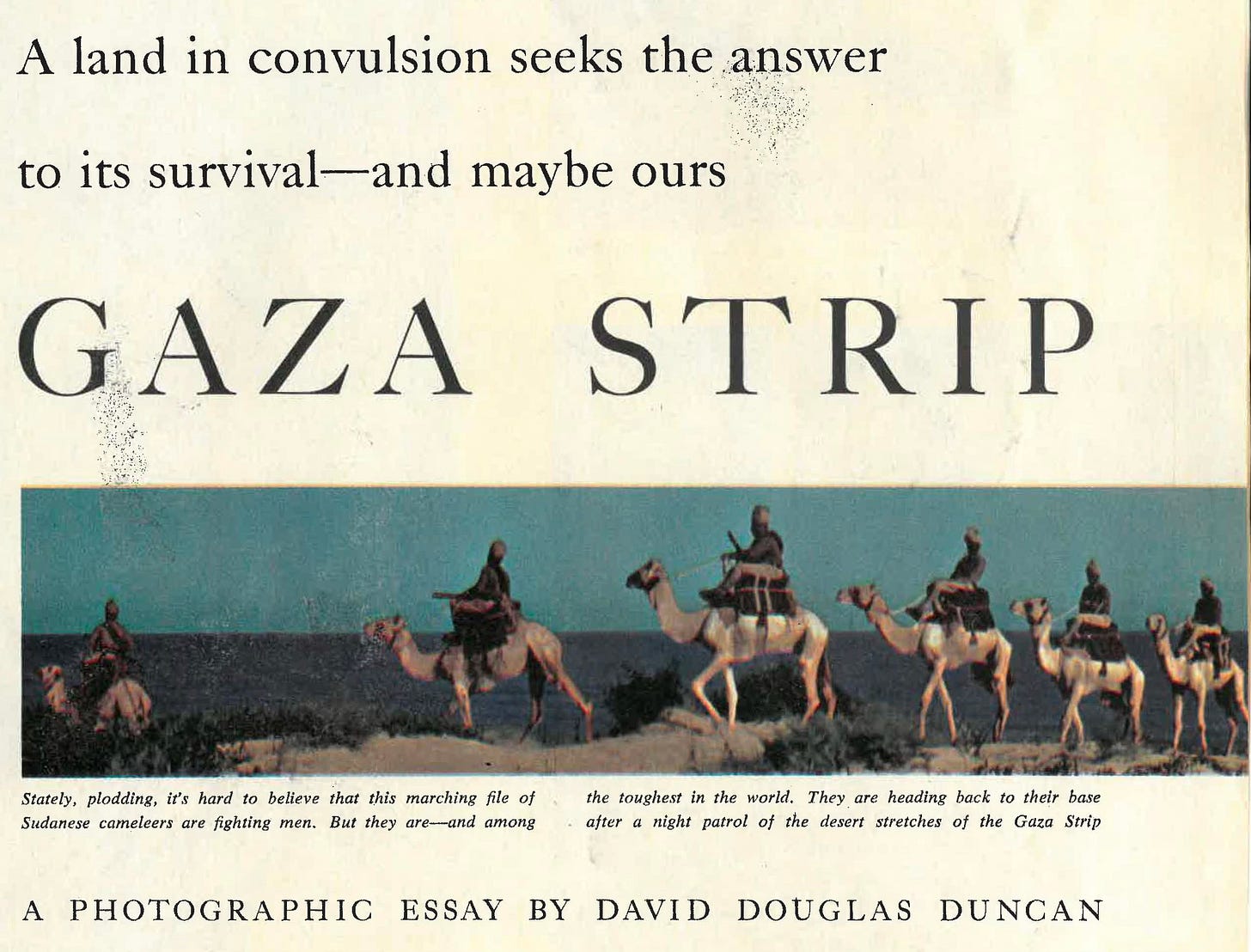

In August 1956, Collier’s magazine published a powerful 12-page photo essay by David Douglas Duncan titled simply: “Gaza Strip.” The cover, featuring a Sudanese cameleer serving as part of the Egyptian military, declared Gaza the “Middle East’s Tinderbox.” Alongside a glamorous feature on Marilyn Monroe, this cover image captured an explosive and overlooked frontier: a densely populated, traumatized landscape still reeling from the 1948 Nakba and teetering on the brink of another war.

Gaza, 1956: A Geography of Displacement

In the wake of the 1948 Nakba, over 200,000 Palestinians—expelled from cities and villages often within walking distance of Gaza—found themselves trapped in a narrow coastal strip just 25 miles long. Many tried to return to their homes to harvest their crops or retrieve belongings, only to be met with Israeli gunfire or landmines. Israel labeled these acts of return as “infiltration.” The borders were drawn not by consensus, but by ceasefire lines that sealed Gaza off from the rest of historic Palestine. From 1948 to 1967, Gaza remained under Egyptian military and civilian administration—but Egypt never annexed the territory, and unlike Jordan in the West Bank, it did not erase Palestinian political identity.

The Photographer: David Douglas Duncan

Duncan’s career spanned several major wars and moments of political upheaval. A former Marine Corps combat photographer, he covered WWII in the Pacific, the Korean War (producing the seminal This Is War!) and later, the Vietnam War, where he turned against U.S. policy. He was the first American photographer allowed into Gaza by the Egyptians—a sign of both his reputation and the political weight of the story. His lens, sharpened by the intimacy of war and displacement, saw Gaza not as a curiosity, but as a human and political emergency.

Gaza, Before the Flood

Coverage on Gaza—then and now—has often lacked nuance, context, and the depth of Palestinian perspective. It’s typically either flattened into crisis headlines or framed through the distorted lens of strategic interest. Rarely is Gaza allowed to speak in its own voice, as a place shaped by history, dislocation, resistance, and humanity. But in 1956, David Douglas Duncan—an American photojournalist best known for his combat photography—did something rare: he entered Gaza not to exoticize it, but to witness it.

His photo essay, published in Collier’s just months before the Suez War and the Israeli-British-French invasion of Gaza and Sinai, is one of the most remarkable and overlooked visual records of Palestine’s midcentury condition. Duncan visited Gaza during a critical interwar period, at a time when the consequences of the 1948 Nakba were still fresh and unresolved. He understood immediately that Gaza was not simply a flashpoint—it was a product of arbitrary violence and abandonment, of borders drawn in war and closed in denial.

What makes this essay so important is that Duncan did not treat Gaza as an accident of geography or a footnote to Cold War geopolitics. He saw it as what it was: a living archive of the Nakba, a capsule of historical displacement, and a powder keg for future war. He captured not just the tents and the refugees, but the deep rhythm of Palestinian life under siege—where people raised children, worked the sea, worshiped, grieved, and endured.

And he was prophetic. In his opening lines, Duncan wrote:

It is a recurrent irony of history that big wars breed in little places. World War I had its Sarajevo, World War II its Danzig. The next war may well erupt from such a slender rectangle of rolling plain and naked desert as the Gaza Strip.

An area brought into being by the truce lines of the Arab-Israeli armistice of 1949, the Gaza Strip is only 25 miles long, an average of five miles wide. Its Egyptian military government rules an Arab population of around 312,000. Only 95,000 are original settlers. The rest are refugees, driven into Gaza’s sandy and desolate embrace by war in the Holy Land.

Gaza as an arena of man’s violence toward man goes back to earliest record. The Philistines operated from it against the Israelites. Here Samson brought down the temple in an epic finale. The Gaza road, an easy corridor between north and south, echoed to the pounding legions of the Pharaohs, of Babylon, Persia, Assyria, Alexander the Great, the Crusaders, the Turks and the British.

Today, once again, violence pervades Gaza. Its bitter spirit rides high in the people—the Arabs bereft of their homes, the Israelis within sighting distance across the mere furrow of the border. Its ugly outbreaks recur in ominous pattern: raids, fusillades, attacking patrols, casual deaths. No man can say when it might widen and overflow and engulf us all. (Collier’s, p. 57)

This metaphor—overflowing—is haunting in retrospect. Nearly 70 years later, Gaza is still overflowing: with displacement, grief, memory, resistance, and now rubble. In the past 18 months alone, the flood has indeed engulfed the region, and with it, global conscience. The nightmare Duncan foresaw—the one birthed from the ongoing Nakba—was never an isolated disaster. It was, and remains, a world-shaping force.

His essay, then, is not just a snapshot of Gaza in 1956. It is a warning that was not heeded. A document that did not disappear. A lens that still sees.

What follows is a guided walkthrough of Duncan’s photo essay as it appeared in Collier’s—with the full original text and captions preserved, and brief commentary to frame each section and its historical significance.

The Land

Introduction: This section introduces readers to Gaza’s terrain—harsh, sun-scorched, and overburdened. It captures the connection between land, sustenance, and resistance, emphasizing how limited resources and forced overcrowding shaped the political and human landscape.

Most of the Gaza Strip is barren, unrewarding land. The sun scorches and the rains seldom come. In the north are a few pockets of rich, dark soil in which grains and beans, orange and olive trees grow well. But the proportion of productive acreage is pathetically small, and the living correspondingly harsh.

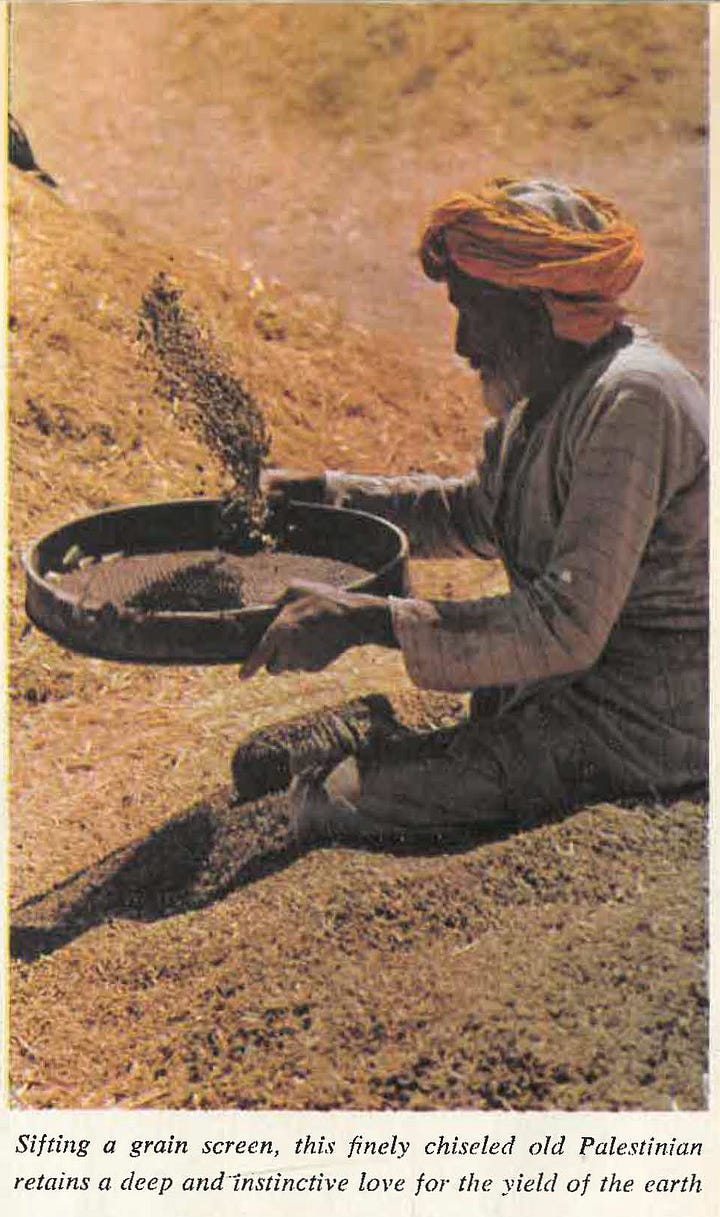

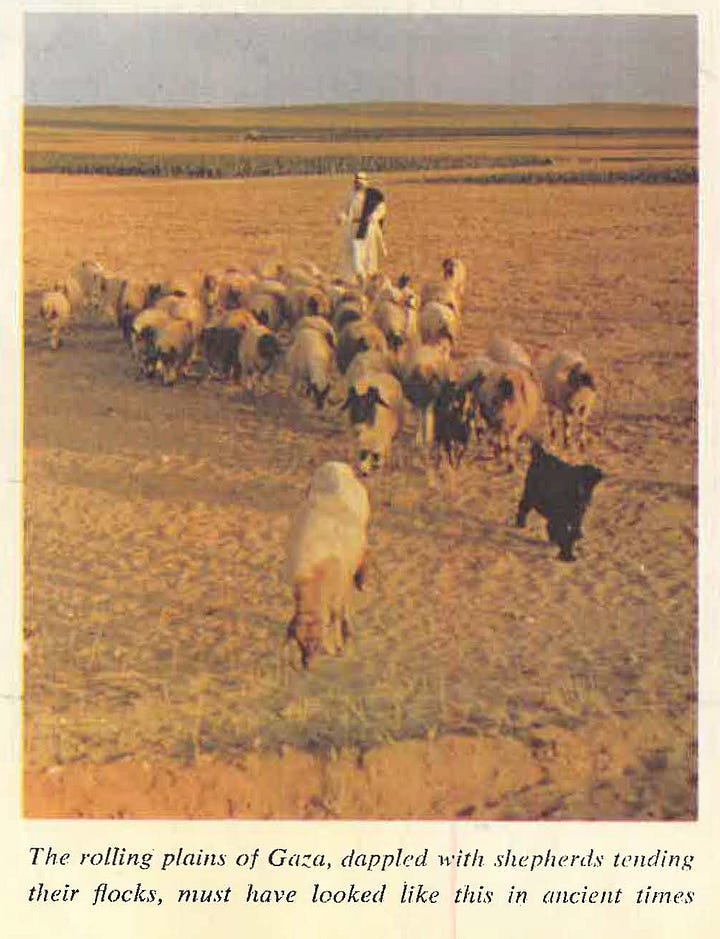

On the plains stretching eastward to Beersheba, the late-afternoon sunlight turns the land into carpets of rich topaz and orange; the dusk turns it into magenta. So must Gaza have looked in Biblical days. Even the people seem the same: a gnarl-fingered, gold-turbaned patriarch still works for his daily bread by sifting grain kernels from trash; a Bedouin shepherd grazes his flock in a parched field of stubble; a peasant farmer walks his donkeys in eternal, pathless threshing circles.

The slim yield of Gaza’s earth—additionally burdened by the refugee influx—is responsible for much of its violence today. Israel complains of Arab infiltrators gleaning barley and reaping wheat. On the Gaza side of the border the land is cultivated right to the last inch short of the demarcation line. The Israelis have refrained from farming so close. To the Arabs, those untilled acres are almost as infuriating as the Israeli presence itself.

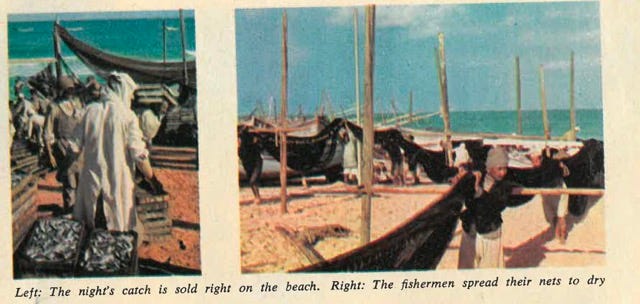

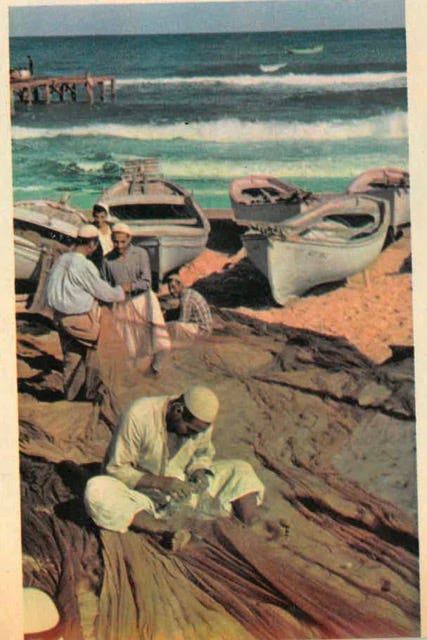

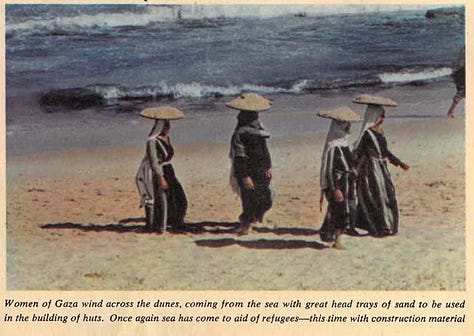

The Sea

Introduction: Gaza’s coastline has always been central to life and livelihood. Duncan’s lens captures not just fishermen and boats, but the militarization of the sea and how this traditional lifeline was turning into a theater of conflict.

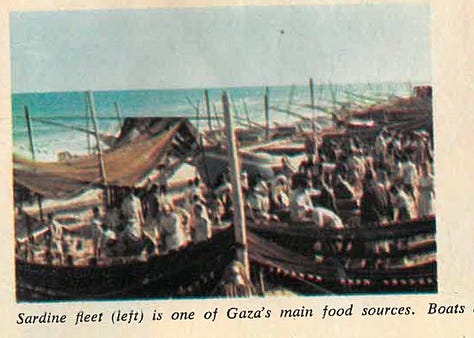

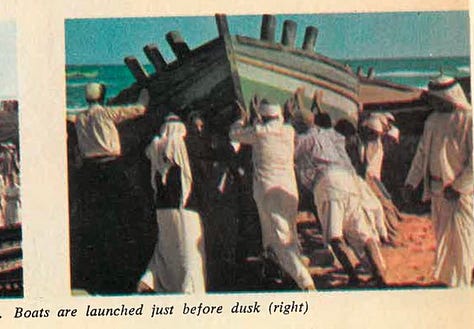

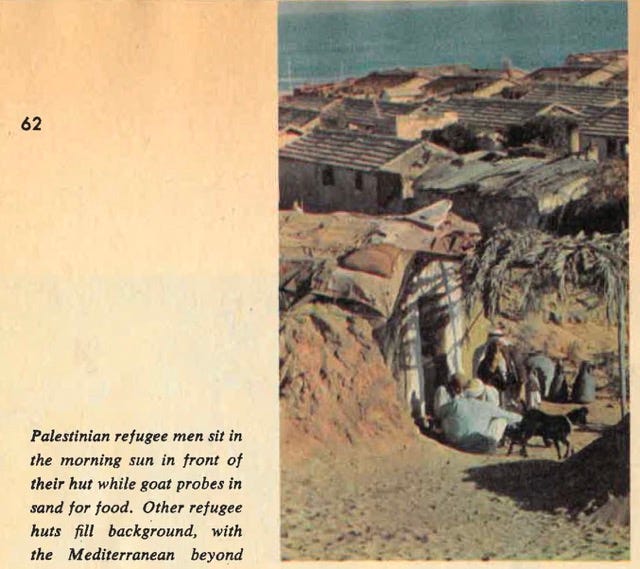

Men of the Holy Land have always been men of the sea as well as men of the fields. For thousands of Palestinian years the Mediterranean—known to the ancients as the Great Sea—has been the bountiful provider for the people who dwell along its shores. Serene, benevolent, its slowly arching combers curving toward horizons far beyond any human vision, it has fashioned the very rhythm of life itself in Gaza.

From its deep waters, misty and blue at sunup, molten copper at sundown, the men of Gaza and their families have traditionally drawn livelihood and sustenance. The sea has given them an abundance of fish; it has even yielded up sand for the construction of their houses.

But these nights the sea of Gaza is a troubled sea. While its fishermen pursue their backbreaking work offshore, the slopes of its beaches are honeycombed with guns of the Egyptian coast artillery, and its dunes are patrolled by Sudanese cameleers on the watch for smugglers trying to break the blockade against Israel. At least temporarily, the quiet sea has fallen victim to the frailties of man.

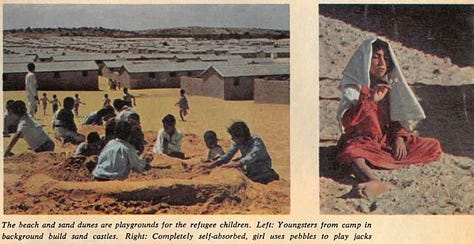

The Refugees

Introduction: This section is the emotional core of Duncan’s photo essay. It documents the UN refugee camps, the unrelenting despair, the makeshift schools, and the simmering anger. His photographs humanize statistics and restore voice to the displaced.

Nothing is wasted in the Gaza Strip—nothing, that is, but life itself.

Of all the troubles in this troubled land, none is worse than the dilemma of the people: not only the refugees, torn from their moorings, still—after eight years—awaiting the day when they can “go home,” but also the original Gaza residents whose meager country they must now share.

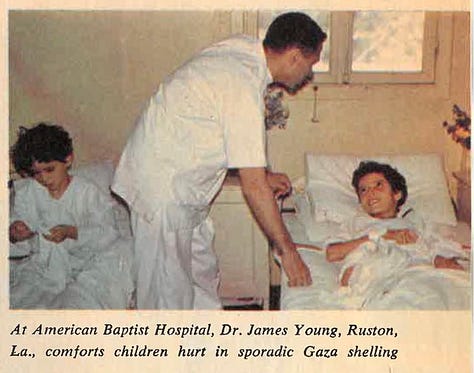

For the 217,000 Arab refugees (more than double the number of natives) the United Nations Relief and Works Agency has set up eight camp communities—endless rows of hut-homes made of tiny concrete blocks with sheet-metal roofs. From UNRWA, too, the refugees get medical care, schooling, kerosene and blankets, and food, including flour, milk, sugar, rice, oils and fats.

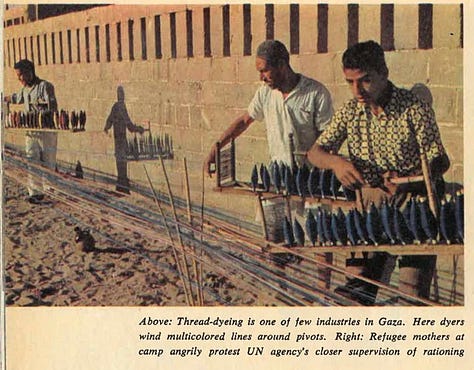

But except for jobs in the camp administration, relief officials cannot provide the refugees with livelihoods. A lucky few work as cotton-yarn dyers or peddle goods along the main street of Gaza town. But there are 55,000 men of fifteen and over among the refugees. Most are without hope; few are without anger; and none without black frustration.

It is rumored that President Nasser of Egypt intends to form a Palestine Government-in-Refuge, elected from the refugees themselves. Until some such means is found to lift the spirit, the prolonged idleness of the able-bodied will remain perhaps the greatest single threat to peace in the Middle East.

⟶ Part II of this series will continue next weekend, exploring the remaining sections of David Douglas Duncan’s photo essay and what it reveals about Gaza’s past and present.

💡 If you value this kind of research, archival storytelling, and historical analysis, consider subscribing to support my work. Your support helps sustain deep, independent writing on Palestine and beyond.

Thank you for this!

It's hard to believe that anyone can survive there. Now I can see how the Palestinians have survived.

It's too bad the spoiled (in all ways) zionists don't now have to start from scratch.

G-d bless the true people of the desert.